What is pre-eclampsia?

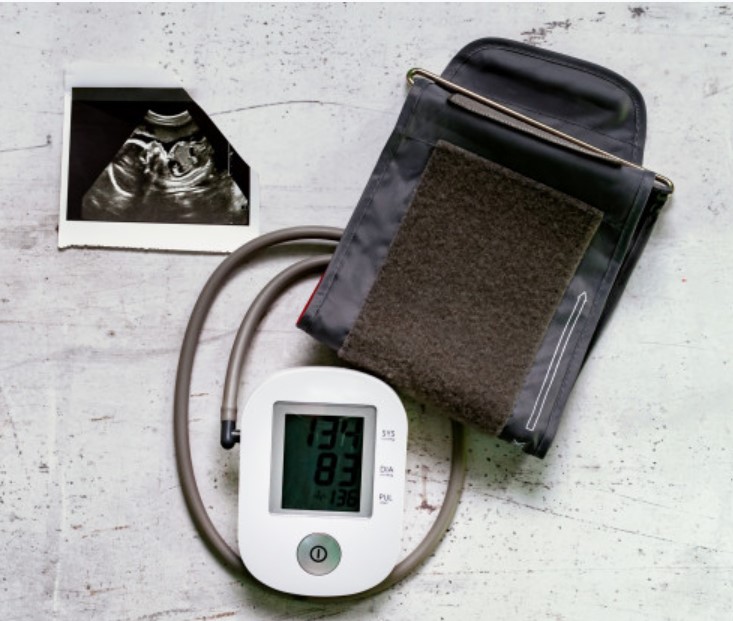

Pre-eclampsia is a condition that typically occurs after 20 weeks of pregnancy which is defined as the combination of raised blood pressure (hypertension) and protein in the urine (proteinuria). The exact cause of pre-eclampsia is not well understood.

Quite often pregnant women could be asymptomatic and pre-eclampsia may be picked up at the routine antenatal appointments when you have your blood pressure (BP) checked and urine tested. This is why you are asked to bring a urine sample to every antenatal appointment.

Why do you need to know if you have pre-eclampsia?

Pre-eclampsia is common, affecting between two and eight in 100 women during pregnancy. It is usually mild and normally has very little effect on pregnancy, however, it is important to know if you have the condition because, in a small number of cases, it can develop into a more serious illness. Severe pre-eclampsia can be life-threatening for both mother and baby.

Around one in 200 women (0.5%) develop severe pre-eclampsia during pregnancy. The symptoms tend to occur later on in pregnancy but can also occur for the first time only after birth. The symptoms of severe pre-eclampsia include:

- Severe headache that doesn’t go away with simple painkillers

- Problems with vision, such as blurring or flashing before the eyes

- Severe pain just below the ribs

- Heartburn that doesn’t go away with antacids

- Rapidly increasing swelling of the face, hands or feet

- Feeling very unwell.

- Decreased levels of platelets in your blood (thrombocytopenia)

- Impaired liver function

- Shortness of breath, caused by fluid in your lungs

These symptoms are serious and you should seek medical help immediately and if in any doubt you should contact your obstetrician. If left untreated, preeclampsia can lead to serious, even fatal, complications for both you and your baby.

In severe pre-eclampsia, other organs, such as the liver or kidneys, can sometimes become affected and there can be problems with blood clotting. Severe pre-eclampsia may progress to convulsions or seizures before or just after the baby’s birth. These seizures are called eclamptic fits and are rare, occurring in only one in 4000 pregnancies. If you have preeclampsia, the most effective treatment is delivery of your baby.

How may pre-eclampsia affect your baby?

Pre-eclampsia affects the development of the placenta, which may prevent your baby growing as it should. There may also be less fluid around your baby in the womb.

If the placenta is severely affected, your baby may become very unwell. In some cases, the baby may even die in the womb. Monitoring aims to pick up those babies who are most at risk.

Who is at risk of pre-eclampsia and can it be prevented?

Pre-eclampsia can occur in any pregnancy but you are at higher risk if:

- Your BP was high before you became pregnant (essential hypertension).

- You pregnancy induced hypertension or pre-eclampsia in previous pregnancy.

- You have a medical problem such as kidney problems or diabetes or a condition that affects the immune system, such as lupus.

If any of these apply to you, you should be advised to take aspirin (150 mg) once a day from 12 weeks of pregnancy until delivery, to reduce your risk.

The importance of other factors is less clear-cut, but you are more likely to develop pre-eclampsia if more than one of the following applies:

- This is your first pregnancy

- You are aged 40 or over

- Your last pregnancy was more than 10 years ago

- You have a BMI (body mass index) of 35 or more

- Your mother or sister had pre-eclampsia during pregnancy

- You have twin pregnancy.

If you have more than one of these risk factors, you may also be advised to take aspirin once a day from 12 weeks of pregnancy until delivery.

How is pre-eclampsia monitored?

If you are diagnosed with pre-eclampsia, you should attend your obstetrician will make a plan for regular appointments in order to monitor your BP and your blood tests. If you have to be admitted in the hospital, your BP will be checked regularly and you may be offered medication (antihypertensives) to help to control it. Your urine will be tested to measure the amount of protein it contains and you will also have blood tests done. Your baby’s heart rate will be monitored continuously with a cardiotocograph (CTG) and you will have ultrasound scans to measure your baby’s growth and wellbeing.

You will continue to be monitored closely to check that you can safely carry on with your pregnancy. This may be done on an outpatient basis if you have mild pre-eclampsia. You are likely to be advised to have your baby at about 37 weeks of pregnancy, or earlier if there are concerns about yourself or your baby. This may mean you will need to have labour induced or, if you are having a caesarean section, this should be brought forward.

What happens if I develop severe pre-eclampsia?

If you develop severe pre-eclampsia, you will be looked after by a specialist team. Each pregnancy is different and the exact timing will be individualised depending on your own situation, however the only way to prevent serious complications is the delivery of your baby.

Treatment for pre-clampsia includes medication (either tablets or via a drip) to control your BP and occasionally you might be given medication (magnesium sulphate) to prevent eclamptic fits if your baby is expected to be born within the next 24 hours or if you have experienced an eclamptic fit. Close monitoring should be undertaken on the labour suite and in more severe cases, you may need to be admitted to an intensive care or high dependency unit.

What happens after the birth of your baby?

In most cases pre-eclampsia usually resolves following the birth of your baby. Occasionally, if you have severe pre-eclampsia, complications may still occur within the first few days, therefore so you will continue to be monitored closely for several days and you may need to continue taking medication to lower your BP. If your baby has been born early (< 37 weeks) or is smaller than expected, he or she also may need to be monitored. There is no any reasons why you should not breastfeed should you wish to do so.

When you go home, you will be advised on how often to get your blood pressure checked and for how long to take your medication. A follow-up with your obstetrician 6-8 weeks after birth for a final blood pressure and urine check. During this consultation your obstetrician will discuss the condition again and what happened. If you are still on medication to treat your blood pressure 6 weeks following childbirth, or there is still protein in your urine on testing, you may be referred to a specialist.

Are you high risk of getting pre-eclampsia in a future pregnancy?

Overall, one in six women who have had pre-eclampsia will get it again in a future pregnancy.

Of women who had severe pre-eclampsia, or eclampsia:

- One in two women (50%) will get pre-eclampsia in a future pregnancy if their baby needed to be born before 28 weeks of pregnancy

- One in four women (25%) will get pre-eclampsia in a future pregnancy if their baby needed to be born before 34 weeks of pregnancy

You should be given information about the chance, in your individual situation, of getting pre-eclampsia in a future pregnancy and about any additional care that you may need. It is advisable to contact your obstetrician as early as possible once you know you are pregnant again.